RONDELI BLOG

Why the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway Matters More than Ever

Soso Dzamukashvili, Contributing Researcher, Central and East European Studies Specialist

Why the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway Matters More than Ever

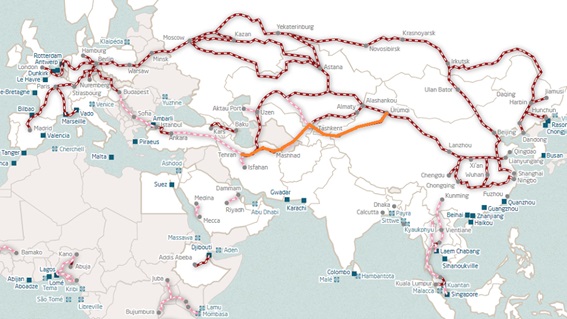

Almost a decade has passed since China set to create a diversified network of transportation routes to connect the country with Western markets – its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Immediately after its launch, the Central Asian countries were envisioned as one of the major transit links in the project. Infrastructure projects were predicated on the notion of Central Asia’s importance as a transit hub between China and Europe. While most attention was directed towards Kazakhstan, both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan remained enthusiastic about their roles in the development of Chinese transportation and trade routes, eyeing opportunities for their economies.

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan corridor, often referred to as the CKU, has been at the center of their focus. A project to connect the three countries by railway predates the Belt and Road Initiative, going back to 1997. It nevertheless remained dormant – mainly due to internal political instability in Kyrgyzstan between 2005 and 2010. However, after then Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev made an official visit to Beijing in June 2012, the project was revitalized. Uzbekistan also reaffirmed its interest in seeing the project implemented.

The potential of the route has substantially increased amid the current Russian aggression in Ukraine and a plethora of tough sanctions imposed by the US and the EU over the Kremlin. The Northern Corridor via Russia, which has long dominated transit between east and west, is bound to lose its importance. This significantly increases the prominence of the corridor crossing Central Asia and the South Caucasus – the Middle Corridor – which has a real advantage to emerge as a competitive route and become one of the main transit corridors allowing goods to arrive in Europe from Asia.

The Middle Corridor is the shortest way between the two continents and can allow cargo to be transported merely in 15 days. However, the infrastructure issues, the absence of a deep-sea port in Georgia and various political issues have impeded the overall importance of the route. Now, as Russia and Belarus are severely sanctioned and isolated, the Middle Corridor could be effectively exploited by the EU along with China and other East Asian countries as the main alternative route.

A Missing Piece of the Puzzle

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway (CKU) has been under discussion for almost 25 years. Despite numerous high-level meetings, the three countries have failed to reach a consensus on the route, railway tracks and sources of funding, as well as to address ecological, geopolitical and national security concerns.

The launch of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative gave the project further impetus. In 2016, Uzbekistan received financial assistance from Beijing in order to complete the Angren-Pap tunnel to connect with a railroad in Kyrgyzstan, a railway which has, however, yet to be constructed. As such, the current CKU corridor is mere as a multimodal transport route as no through-rail connection exists directly linking China and Uzbekistan. Its total length reaches 4,380 kilometers and connects the Chinese city of Lanzhou to Uzbekistan’s capital Tashkent.

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan corridor as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (Source: UIRR)

On its inauguration in June 2020, 230 tons of cargo worth 2.6 million US dollars was transported from Lanzhou by rail to the Kyrgyz border where it was reloaded onto trucks and driven via Kyrgyzstan to the town of Osh after which it was carried once again by rail to Uzbekistan. The route is intended to transport consumer goods from China to Central Asia and take food products, minerals and oil exports the other way. It is seen as a win-win opportunity for all participants as it has the potential to directly link the region to Western Europe through the South Caucasus and Turkey.

Uzbekistan is already connected to Turkmenistan and Iran, and once the Kyrgyz section of the railway is completed, the CKU railway will become one of the shortest routes between China and Western Europe, making Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan key transit countries for Chinese exports. The corridor would offer Bishkek transit fees and new employment opportunities which could help the country’s economy, which has been riddled with foreign debt, finally witness a substantial recovery.

Even though Uzbekistan already has a rail connection with China via Kazakhstan, it is on average 20 per cent more expensive than the route through Kyrgyzstan with cargo currently being carried by trucks. Transportation of goods on a hybrid rail-road route takes from a full week to ten days in a single direction. A railroad connection between Tashkent and Lanzhou, however, would require much less time and could further boost the importance and attractiveness of the CKU corridor.

The leaders of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan frequently emphasize the need to complete the CKU railroad. On August 6 2021, at a meeting of Central Asia’s heads of state in Turkmenistan, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev said that the route would help create “an extensive and integrated transport system” capable of becoming a key transit hub on the Eurasian continent. Yet the positive hype and never-ending negotiations remain the only achievements of the railway project so far.

An Unexploited Potential

While the transportation corridor could present myriad opportunities for participant states and the region at large, especially when the future of the Northern Corridor seems to be vague, it is dubious that the construction of the railroad can be completed soon. Major issues that hinder railway construction include political instability, underdeveloped transport infrastructure and, above all, financial issues in Kyrgyzstan.

The Kyrgyz authorities have for years been promising to complete the railroad, albeit without ever securing the required financial resources. China has long been seen as the only participant that could resolve the funding issue. However, Kyrgyzstan’s foreign debt reached 4.8 billion US dollars in 2021 and around 40 per cent of that – 1.8 billion US dollars is owed to the Export-Import Bank of China. Afraid of falling into a “debt trap,” Bishkek appears to have stopped viewing Beijing as a potential funding source for the railway. In a June 2020 statement, the executive director of the Kyrgyz National Railway Company did not mention China among the funding partners for the project, only Uzbekistan and Russia.

Proposed Routes of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway (Source: The Third Pole)

Nevertheless, Uzbekistan might not be capable of substantially contributing to the project, estimated at 4.5 billion US dollars. Tashkent has declared its readiness to participate in the construction of “certain sections” of the railway but it might not be sufficient for the full multi-billion construction. Moreover, the Uzbek authorities still need to seek international financial assistance to partially fund the project and work out with the Kyrgyz government ways of implementing transit fees to pay back the construction.

The future of the Middle Corridor largely depends on the finalization of the construction of the CKU corridor. It could be effectively exploited by the EU along with China and other East Asian countries as the main alternative route between Europe and Asia. It is also part of Beijing’s ambitions to promote alternative routes of BRI. Therefore, it would be reasonable if the EU along with China actively revitalizes its intentions to cooperate with the countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus with regard to further investments in the development of free and sustainable transit along the corridor. Considering energy resources in Azerbaijan and Central Asia, the EU could also diversify its energy supplies and decrease its dependence on Russian gas, which according to statements of EU officials at the Versailles Summit, has become a new priority for the EU in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Related posts

- Hungary’s illiberal influence on Georgia’s European integration: a worrying pattern

- NATO Summit in Vilnius: Results and future perspectives

- Expected Political Consequences of the Restoration of Railway Communication Between Russia and Georgia through Occupied Abkhazia

- Germany’s National Security Strategy – The First Strategic Steps

- The Turkish Economy following on from the Elections

- The 11th package of EU sanctions and Georgia

- The Recent Decision of Saudi Arabia and its Impact on the Energy Market

- The Results Turkish Presidential and Parliamentary Elections

- The Occupied Tskhinvali Region: Gagloyev’s First Year

- Is Ukraine Winning the War and What Might Russia's Calculation Be?

- Russia's Diplomatic Offensive in Africa

- Russia’s New Foreign Policy Concept and the Occupied Regions of Georgia

- Europe's Energy Security – How is the Strategic Goal Progressing?

- Then what does Putin's arrest warrant change?

- Lukashenko's Battle with Belarusian Identity

- Why Estonia’s parliamentary elections matter for Ukraine and Eastern Europe?

- What does China's initiative to normalize relations between Iran-Saudi Arabia actually mean?

- Is America’s Ukrainian War Fatigue” Real?

- Power of the people in Georgia: The EU must remain vigilant

- Impact of the Cyprus Election Results on the Security of the Eastern Mediterranean Region

- Who will be affected and what problems will they face if the so-called

- Dynamics of China-Russia relations against the backdrop of the Russo-Ukrainian War

- The Russia-Ukraine War and Russia's Long-Term Strategic Interests

- On the "Agent of Foreign Influence'' Bill and Its Disastrous Consequences for Georgia

- Hybrid War with Russian Rules and Ukrainian Resistance

- Moldova’s challenges alongside the war in Ukraine

- How the Sino-American Competition Looks from Tbilisi

- Is Israel's New Government Shifting its Policy towards the Russia-Ukraine War?

- Geopolitics, Turkish Style, and How to React to It

- What is Belarus preparing for

- Belarus and Russia deepen trade and economic relations with occupied Abkhazia: A prerequisite for recognition of Abkhazia's “independence”?

- "Captured emotions" - Russian propaganda

- The Eighth Package of Sanctions - Response to Russian Annexation and Illegal Referendums

- What’s next for Italy’s foreign policy after Giorgia Meloni’s victory?

- Lukashenko's Visit to Occupied Abkhazia: Review and Assessments

- Occupied Abkhazia: The Attack on the Civil Sector and International Organizations

- Tajikistan’s Costly Chinese Loans: When Sovereignty Becomes a Currency

- What could be the cost of “Putin’s face-saving” for European relations

- In line for the candidate status, Georgia will get a European perspective. What are we worried about?

- Political Winter Olympics in Beijing

- An Emerging Foreign Policy Trend in Central and Eastern Europe: A Turn from China to Taiwan?

- Can Georgia use China to balance Russia?

- The West vs Russia: The Reset once again?!

- Securitization of the Arctic: A Looming Threat of Melting Ice

- USA, Liberal International Order, Challenges of 2021, and Georgia

- The Political Crisis in Moldova: A Deadlock without the Way Out?

- Georgia's transit opportunities, novelties and challenges against the backdrop of the pandemic

- ‘Vaccine Diplomacy’: A New Opportunity for Global Authoritarian Influence?

- Deal with the ‘Dragon’: What Can Be the Repercussions of the China-EU Investment Agreement?

- Vladimir Putin's Annual Grand Press Conference - Notable Elements and Messages

- Kyrgyzstan in a Political Vortex: When Two Revolutions are “Not Enough”

- Trio Pandemic Propaganda: How China, Russia and Iran Are Targeting the West

- Decisive Struggle for the Independence of the Ukrainian Church

- Current Foreign Policy of Georgia: How Effective is it in Dealing with the Existing Challenges?

DYNAMICS AND STRUCTURE OF GEORGIA‘S TRADE WITH THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (Before and After the full-scale Russian Invasion in Ukraine)

DYNAMICS AND STRUCTURE OF GEORGIA‘S TRADE WITH THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (Before and After the full-scale Russian Invasion in Ukraine)  The ZEITENWENDE in German Foreign Policy And The Eastern Partnership

The ZEITENWENDE in German Foreign Policy And The Eastern Partnership